The Fleischmann House

Peekskill, NY

Gustav Fleischmann, Jr.

Gustav Fleischmann, Jr. was born in 1885 in Buffalo, New York, as the son of a successful spirits manufacturer who owned the Buffalo Distilling Company. His father was the younger brother of Charles and Maximillian Fleischmann, who went into the yeast and distilling business before him, and founded the commercial empire that became the Fleischmann Company.

When Gustav Jr. came of age, he joined his father’s company in 1903 and learned the business. He left Buffalo in 1907 to work for his uncles at the Fleischmann-Clarke Company in San Francisco, where its plant had burned down during the great fire of 1906. He was tasked with helping to rebuild it, and continued working there for another five years. He left San Francisco to become sales manager for the Fleischmann Company in Baltimore in 1912, but several years later was promoted to a similar post in Philadelphia. Following prohibition in 1918, he transferred to Chicago, where he gained experience in yeast and vinegar production.

In 1920, he was named General Manager of the Fleischmann Company's massive yeast plant in Peekskill, NY. The company became a division of Standard Brands during his 33-year tenure at the plant, and he was subsequently named Executive Vice President. He retired in 1953 after working 50 years in the industry.

Early History of the Fleischmann Company

Before locating in Peekskill, the first iteration of the company began in the 1870s with operations in Cincinnati, OH and Long Island, NY. The company was founded by Hungarian immigrants James Gaff and Charles and Maximillian Fleischmann. The Fleischmann brothers were born to a Hungarian baker who taught them the art of yeast production before they immigrated to America. After the brothers’ arrival in New York, they partnered with Gaff to introduce the first commercially reliable yeast to American baking, and became extraordinarily successful. As noted in Christina Klieger’s book, The Fleischmann Yeast Family:

Most American home bakers had struggled to make bread with various sourdough starters, liquid concoctions of sugar, malt, flour, and potatoes, or the foamy brewer’s yeast skimmed from fermenting ale, or other such potions… Even if some leavening action was achieved by these various wild strains of yeast and bacteria, the microbes succeeded in adding their own waste products to the brew, resulting in unpredictable bitterness, sourness, and other off-tastes in the finished baked goods...

What was certain in the founding story was that Charles and Max arrived in an America that had no commercial yeast production... The keys to their business success were, one, the reliability of the yeast product they introduced to America, which had more uniform leavening power than any homemade alternative; and two, the capacity of the delivery service, which provided live, active yeast to their most critical customers, the commercial bakers, along with brand name recognition.

James Gaff died in 1879, having become a major figure in American business life. However, his heirs did not wish to continue the enterprise he had built with the Fleischmann brothers, and they sold their interest in the company to Charles and Max for $500,000.

The Fleischmann brothers reorganized the business as a proprietorship and subsequently changed the name to Fleischmann & Company. By then it had over 1,000 bakers as clients and an untold number of individuals as customers, to whom it delivered yeast cakes across a growing commercial network that spread throughout the United States.

The Largest Yeast Factory in the World

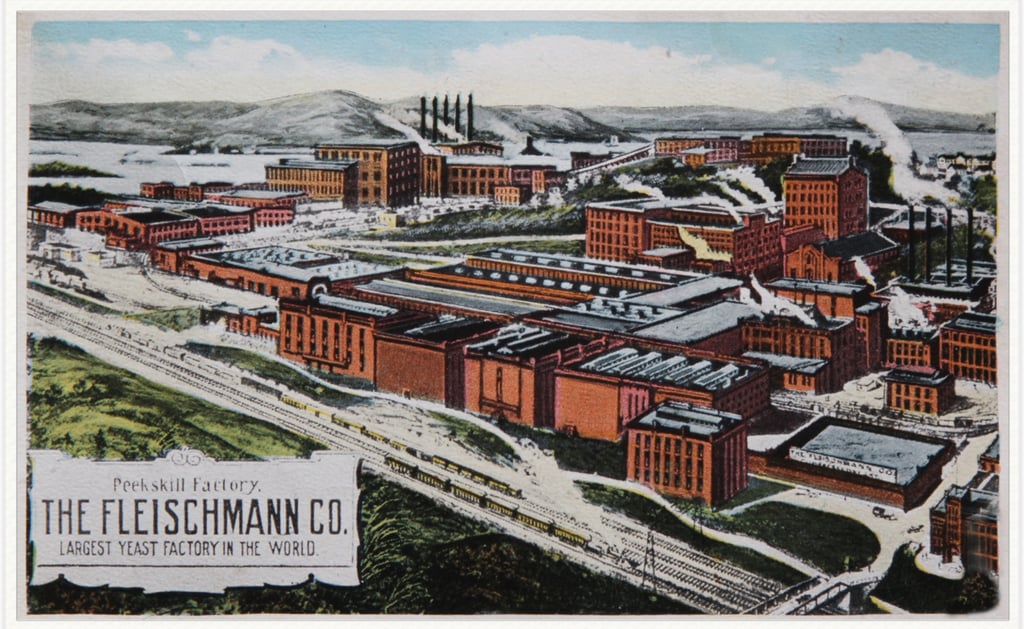

Fleischmann & Company moved its headquarters from Long Island to Peekskill, NY in 1900, at a location on the Hudson River that was later named after the older brother as Charles Point. After operating as a proprietorship, the business was incorporated as the Fleischmann Company in 1905. Illustrated postcards and photographs from the early and mid 20th Century show the Peekskill plant’s immense factories, buildings, grain elevators, distilleries, storage tanks, warehouses, wharves, laboratories, offices, and employee housing. Touted as the largest yeast factory in the world, the plant consisted of 125 buildings connected by two miles of railroad spread across 65 acres of land.

The company’s workforce made the “Fleischmann's” brand a household name throughout the United States, not only through the company’s varied product lines, but also its advertising techniques that were innovative for the time. These included national campaigns that touted the health benefits of vitamin-rich yeast, and featured testimonials and photographs of actual customers. The company also sponsored a pioneering musical variety show broadcast on NBC radio from 1929 to 1939, known as “The Fleischmann Hour” (also known as “The Rudy Vallée Hour”). It became one of the nation’s most popular radio shows, and is remembered for introducing jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong to a national audience.

Charles and Max Fleischmann became extraordinarily successful, joining the ranks of such storied families as the Carnegies and Vanderbilts, and became prominent philanthropists. In 1920, their nephew Gus was appointed as General Manager of the company's Peekskill plant. As an engine that drove the local economy until 1977, the plant produced much of the nation’s yeast, gin, vodka, whiskey, vinegar, malt, and baking powder. It employed thousands of area residents in a wide range of professions, including brewers, distillers, bottlers, packers, dock workers, train operators, truck drivers, mechanics, plumbers, welders, electricians, machinists, pipe fitters, masons, carpenters, builders, draftsmen, engineers, architects, clerks, bookkeepers, accountants, chemists, lawyers, and managers.

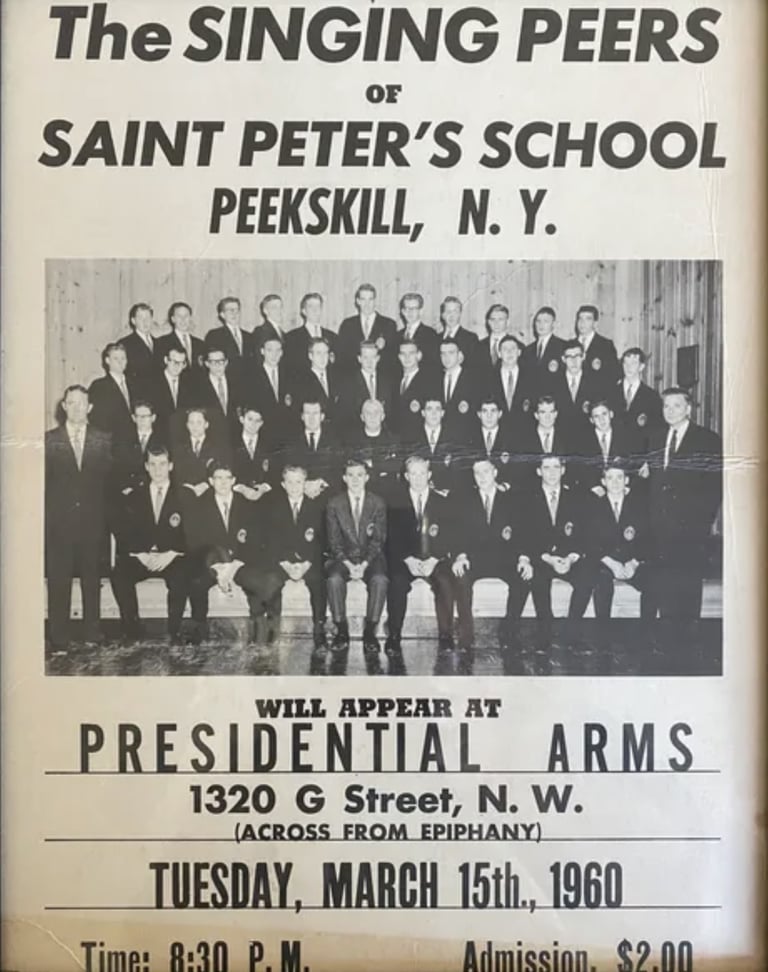

The boys’ education in academic subjects was accompanied by the development of religious and moral character, the teaching of traditional values, and the reinforcement of self-discipline. At the same time, the school used progressive instructional methods, including “corrective reading” techniques pioneered at Columbia University. This included showing students historic films, having them work with their hands on related projects, and reading related works. Music was also a staple of the curriculum, and the school’s glee club, the ‘Singing Peers,’ repeatedly toured the eastern U.S., gaining national attention (and funds) for the school. This included concerts in major cities and performances on radio and television, including recurring performances on Martha Dean’s well-known radio program on WOR. The glee club went on to record two records with R.C.A.

Before the school garnered such national attention, its humble origins began in 1938 when it was temporarily housed in a building loaned by the Episcopal Diocese. The next year the school’s first permanent location was made possible through the purchase of a property with extant buildings that were transformed into classrooms, dorms, dining facilities and offices. Gustav Fleischmann’s role in securing the property is recalled in Rev. Frank Leeming 1966 book on the school’s history. As St. Peter’s rector, Rev. Leeming had tried to secure a mortgage for the new school site, but was turned down by bank after bank due to a lack of collateral. It wasn’t until Mr. Fleischmann agreed to guarantee the first five years’ of loaned principal and interest payments that Westchester County National Bank extended a mortgage to the school for $12,000. Rev. Leeming went on to affectionately recount Gustav Fleischmann’s role on the school’s Board of Trustees, as follows:

St. Peter's School

Gustav Fleischmann was not only a business leader at the local, state and national levels, he was also a prominent civic leader and champion of education. He served as Chairman of the Peekskill Hospital’s Finance Committee, to which he designated $30,000 in grants through the Max C. Fleischmann Foundation. He also served as Chairman of Peekskill’s Red Cross Disaster Committee during the 1940s, which helped local families of GIs who were killed or injured in the war.

However, his most enduring and important role was as founding trustee and first president of St. Peter’s School for boys in Peekskill. Established in affiliation with the Episcopal Church in 1938, the school was founded on the “self-help” model in which students assumed responsibility for caring for buildings, cleaning classrooms, setting and clearing dining tables, washing dishes, and performing other daily chores. The school enrolled both day students from the vicinity and boarding students from elsewhere in New York and from other states and nations.

Mr. Fleischmann has been on the Board since the very beginning, and during my years at the school he was my constant adviser, even though there were times when our relationship was strained. I remember that soon after our move to the new site I spoke to him in my office about an advertising plan I had in mind to increase enrollment. He immediately asked what it would cost, and I said “$875.” In a loud voice he said, “Where the hell are we to get the money?” I’m afraid I lost my temper when I responded, “You know, last night I was driving back to Peekskill from New York City, and there - flashing on and off across the river - was a sign bidding people to buy Fleischmann's Gin. Now, you may know how to make gin, but you don’t know everything about running a school.” He turned and stormed out of my office, but the next morning when I got to my office I found a tin of 50 of my favorite cigarettes on my desk. They were from Gus… We had many differences, but they never affected our friendship and I always knew I could count on him. Even now after retirement, I make no serious decision without talking the matter over with him. Such friends are few and far between.

Gustav served as president of the school’s governing board from its inception until 1947, and a dinner was given by the school in his honor when he passed the president’s torch to another trustee. Yet he continued serving on the board thereafter, and brought substantial financial support to the school through the Max C. Fleischmann Foundation. This included five annual grants of $5,000 from 1953 to 1957.During this period, an interesting facet of the school’s curriculum was its required study of Communism and the threat it posed. As a reflection of the times, it became part of the curriculum in response to the ‘Red Scare.’ But rather than teach an emotional reaction in opposition to communist doctrine, the school emphasized the use of calm discourse and logical reasoning to analyze arguments for and against Communism. As explained in a feature article published by New York’s Daily News, the purpose was to enable students to refute political arguments that favored Communism by intelligently deconstructing them, and to rationally articulate counter-arguments in favor of democratic principles and Christian beliefs.

This had particular local significance following the 1949 “Peekskill Riots” that occurred in opposition to a local concert given by Paul Robeson, in which buses were stoned and cars were overturned. As a nationally acclaimed singer and actor, Mr. Robeson had become controversial for his political views and activities, which included visiting the Soviet Union, and refusing to disavow his membership in the Communist Party. The violent riot that occurred at his Peekskill concert stands in stark contrast to the calm discourse taught by St. Peter’s School.

As the 1950s gave way to the 1960s, the school’s diverse international enrollment grew, as did its facilities, along with its expenses. New property was acquired and buildings were added. Mr. Fleischmann’s support of the school was important to its continuing operations, and he became known as ‘Uncle Gus’ to faculty, staff and students alike. In recognition of his philanthropic support, the school added a library named in his honor in 1963. Thanks in large part to his efforts and those of other trustees, St. Peter’s School educated hundreds of boys who went on to attend the nation’s leading institutions of higher learning.

Yet, despite the trustees’ best efforts, St. Peter’s School was eventually forced to close in 1971 due to the rising costs of maintaining aged and expanded facilities, at a time when the nation’s economy took a downturn and fundraising became more difficult. This coincided with declining enrollment, as attendance at religiously affiliated, same-sex boarding schools began to fall out of favor with the changing times. And yet, during its 33-year history, the school made a lasting impact on its many graduates, who still comprise an active alumni association with periodic reunions, the most recent being held in 2016. It also manages an up-to-date website, one that recalls an educational tradition that was equally concerned with the development of moral character as it was with academic achievement.

Five years after the school’s closing, Gustav Fleischmann passed away in 1976 at the age of 90. He is buried in the local Hillside Cemetery alongside his wife, Marion, whom he survived by five years. Shortly after his death, the Fleischmann Company closed its aging Peekskill plant, and moved its operations to Baltimore. Nearly all of its old factory buildings and offices were subsequently razed, leaving behind just a few brick structures and a single pier named for the company, extending into the Hudson River. Gone are the plant’s factories, grain elevators, storage tanks, assembly lines, train cars, and company trucks that were such a visible and vital part of the local community.

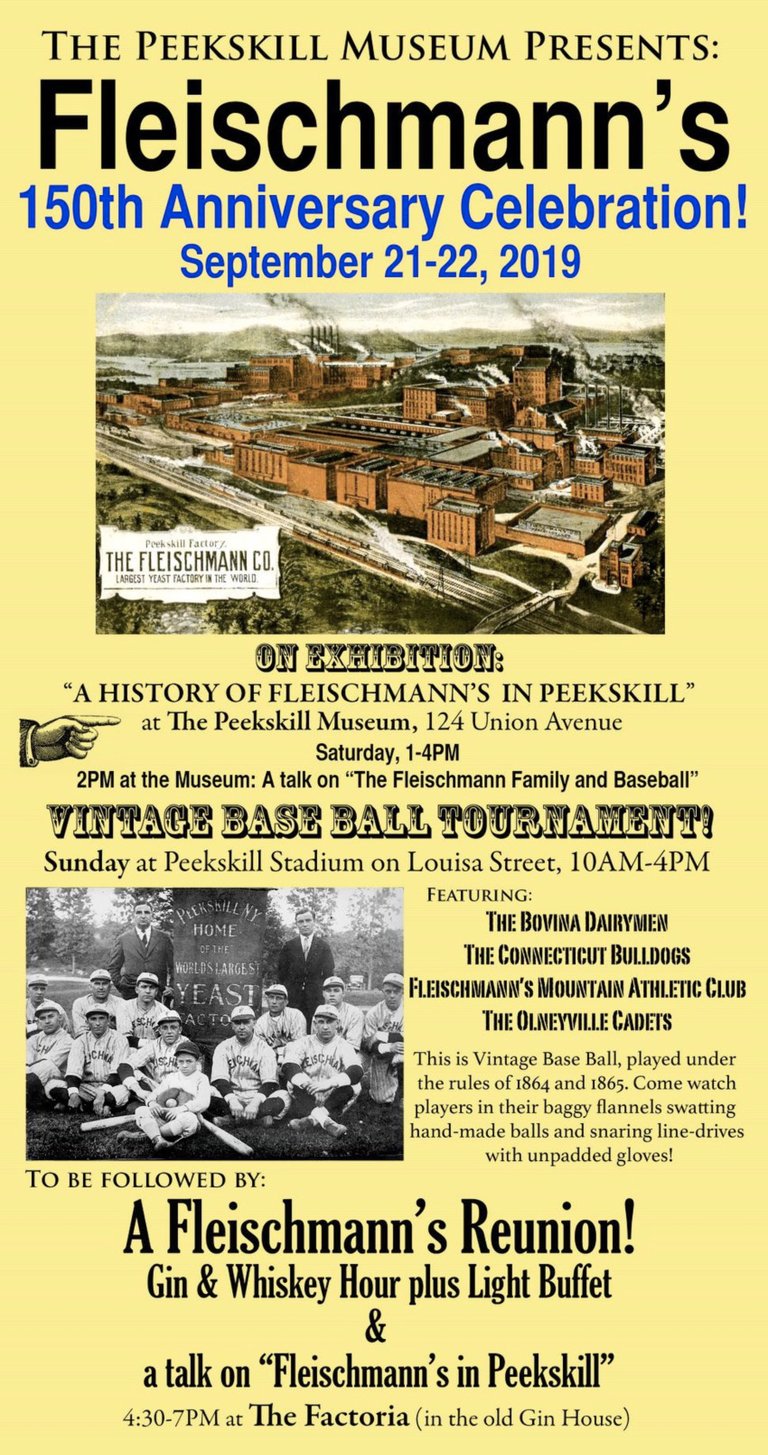

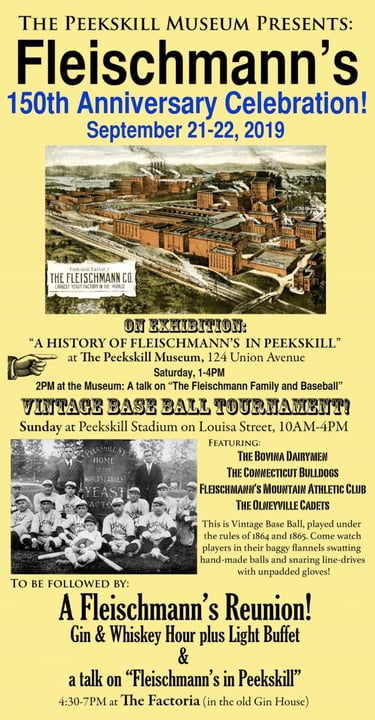

Yet, the Fleischmann House still stands on a hillside overlooking the Hudson River, where the company’s operations once dominated the landscape. The house is one of the last remaining visible reminders of the important role that the Fleischmann family and company played in Peekskill’s industrial and educational history. That history is still remembered by local residents, many of whom attended a weekend celebration of the company’s 150th anniversary which was sponsored by the Peekskill Museum in September of 2019. The weekend’s festivities included a museum exhibit, lectures on the history of the Fleischmann Company, slide presentations, the display of archival photographs, and a dinner reunion on the riverfront at one of the two buildings that are still standing where the original plant was located. Although most of the buildings are gone, the history is etched in Peekskill’s collective memory.

In the early 1940s, the company’s laboratories developed a groundbreaking dry packaged yeast that transformed home and commercial baking. Unlike traditional blocks of compressed moist yeast cakes that had to be chilled, the new powdered dry yeast could be packaged in smaller foil envelopes without the need for refrigeration. This meant that it had a long shelf life and could be transported long distances cheaply and easily.

The U.S. Army and Navy were so impressed with the new. yeast that they gave the employees of the Peekskill plant five awards of excellence for distinguished service on the production front during World War II, and used the yeast to provide bread to armed troops in the European and Pacific theaters of the war.

By the end of the war, Gus Fleischmann’s leadership position within the family enterprise was promoted to First Vice President of Standard Brands, of which the Fleischmann Companies had become one of the largest divisions. He retired in 1953 after working 50 years in the industry, and was feted at a retirement dinner in his honor at Peekskill’s armory, which was attended by 420 friends, colleagues, and civic leaders.

Gustav Fleischmann, Jr.

Postcard of the Fleischmann Company's Peekskill Plant

Rudy Vallée

Fleischmann's Yeast Ad

Playbill for the Singing Peers

For additional historic information, visit the tabs at the top of this page.